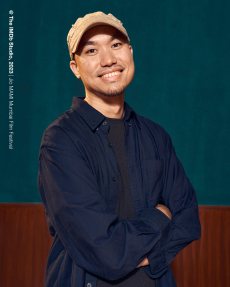

Thai filmmaker Patiparn Boontarig debuts his first feature-length film, the queer romantic drama Solids by the Seashore on March 17 in the UK. I sat down with him to discuss his film, themes and the importance of letting nature take its course.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

—

TACC: When you were creating this movie, were you expecting it to have a big international reaction, or was it filmed with a local audience in mind?

PB: I just have to tell the story I want to tell, with a message that I want to convey. And yeah, I think if it can reach an audience in different countries, and different culture see it, that would be great. I tried to make my film universal enough for an audience to be able to lean into it with their own experiences, and even with their different cultures. I am really excited for this, and to be able to listen to the reaction from the audience in different countries. Sometimes they have different thoughts about the film.

In the film there is a strong environmental and cultural message that must be very personal to the people of Thailand. Are these themes that you expect to translate well to different audiences?

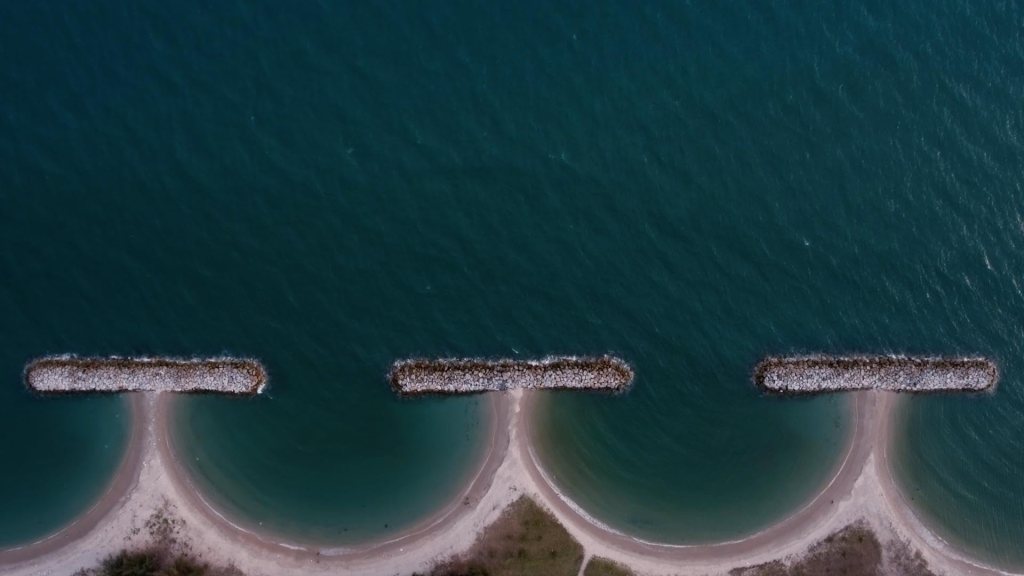

I think that there are two parallel lines: the sea world, and the people. The metaphor is of the relationship between the two characters. They are like the beach and the ocean, where they have put up some walls – of belief, or culture – that prevents them from being natural. I tried to make it a metaphor and also to make an environmental story, of equality and of this relationship. A mix of culture and belief.

These barriers we build, either in nature or in your mind; do you see it as all negative, or are there any positives?

For me it depends. The sea walls are built to protect the beach, but it makes more erosion. If you want to make a sea wall on one beach you have to know the consequences; that you will have to build more and more until it covers the whole beach. You have to make the decision of which beach to protect: we want to protect the road, so maybe the sea wall will be good.

So actually it depends, which is why the end of the film is open-ended and there are no bad guys in the film. They still can choose the conservative ending and it can make her have a good life in another way, but it’s up to her which life she chose. That’s the interesting thing – it’s not positive or negative, but which side you want to be.

On that front, where do you see things going for Shati? What’s your own personal interpretation of the ending?

Uh… [laughs]. The ending for me … I am a politician. Because, as the director, actually I didn’t tell my idea, which is the “real” one. I want to leave it in the audience’s imagination.

Otherwise it becomes canon.

Even for the crew, I didn’t tell them. I let them have their own version. I think the interesting thing in watching my film is that many people will have their own version. I went to one film festival and in a Q&A session, an audience member told me: “I don’t like the ending; her ending up with the guy”. And in another Q&A session, an audience member raised their hand and asked the same question, but another audience member said she thought Shati ended up with the girl. So everyone has their own versions, and that is the right one. It depends on the experiences of the one who watched the film.

In a way that encourages a level of discussion you might not always see in a film.

Yeah, yeah. I think I didn’t want to force the audience in one way, wanted them to have their own thinking. That it can be anything.

As this is a film about two women, and their relationship, how much of a personal element did you put into the story?

Actually, this film is really, really personal to me. Adapted from my own true story, but I twisted in the way that many people won’t see from the outside. But for me, growing up, I was treated like a girl because in my family – my father, brother and everyone who is a guy they have many very masculine personality that is different from me. Like I am more like my grandmother and my mother, more than them. That is how I see what it should be to be a guy and to be a girl. And for me, my personality is more on the side of the women in my family. And also my familiar really strict: the rules from my father that tell me to do this or not do that, and I’m growing up in that frame.

And also I understand how to be like oppressed from someone like have more power. So I understand the story. I mean as much as I can understand – as a guy – but I experienced something that is really similar to that.

One thing I want is to take out all the labels. Like for a guy, one would think: “oh you are a guy, you should be like that: 1,2,3,4,5”, but if you are a girl or if you are LGBT? For me it is not like that, I want to remove those labels, and it is good for humans to just look another human. That’s why I tried to challenge this with this theme, with these two characters. I didn’t want the audience to think about their genders, rather to think about them as two human beings who have feelings for each other. I didn’t use my gender to direct the film, but I used how humanity and how we are treated like.

When you wrote the film, did you see yourself more in the point of view of Shati? Is there a Fon character in your life that you based it on?

[Laughs.] Actually both of them are me in some part, because I think the film tells the story of someone who like has been oppressed from another one. With Fon is it with another artist. Someone pushed them down. I mean these kinds of characters are everywhere, maybe not these two characters. Like everyone has this feeling before. My co-writer [Kalil Pitsuwan], who is Muslim, knows about and tells the Muslim story more, helps me develop the story together. He also experienced some toxic masculinity that we share and put into the film.

Tell me more about the relationship with the sea, or with nature as a whole and how that impacted your film.

Actually the inspiration for the film is from when I went to the city, the big city, to make the documentary about the sea walls. I made one short documentary first and at the time I interviewed the mayor of the city, because he is fighting bad sea walls because they’re not good and cost a lot of money. So it’s like corruption. He’s fighting. After I finished shooting that film, he got shot, and he died. He lost his life protecting the beach. It really shook me, and made me think: “OK I really want to make it bigger than that documentary, and make a feature film and to have a point to make it a metaphor to human life, and to make the sea wall as the background”. So after that I was more in Bangkok, but I don’t like Bangkok much. I go to the beach, and see more nature. After, I made p;ans to make this film so I go back, thinking about Southern Thailand, the ocean. I also do the scuba diving. Actually the footage from underwater is from me. Like I shot it myself. I like nature.

Are you coming down to the UK premiere?

Uh not this time. At first I thought the government will support the travel and everything, but I think their decision was to not provide the support, so I cannot be there I really want to be there. But my actress [Ilada Pitsuwan] will be there. Shati, the main actress, she is studying in the UK, so she will join and you will have a Q&A session with her.

On the topic of your actors, how did you approach the casting for the film?

Actually we did an open call for the characters, and an audition. We did the casting for Shati first. She’s the one who applied for the open call, she actually had done a bit in television but hasn’t acted in film before. She also wanted to try, and she was interested in the topic and message of the film. So she apply to audition, and she really got into the story and background; She’s really like that character. So we picked her first and then we made a call for the artist [Fon, played by Rawipa Srisanguan], and then we tried to match with her. We auditioned many actors with Shati, many times, until we got this one and the chemistry between the two of them is really great. They could be comfortable around each other, at that time we really locked the casting.

Any plans for what’s next?

I have ideas for a new film. My second film. I’m still interested in human themes but now I’ll move from Bangkok to the north of Thailand. To Chiang Rai in the north of Thailand. So I think I’ll make a film about the Kok River and the dam.

It’s working well for you, and there’s a lot you can say about us and our relationship with nature. It’s good to have a theme.

[laughs]

I want to thank you for very much for speaking with me today, and I look forward to seeing what’s next.

Thank you, bye bye.

SOLIDS BY THE SEASHORE is screening at BFI Flare: London LGBTQIA+ Film Festival at BFI Southbank on Sunday 17 and Tuesday 19 of March.

38th BFI FLARE: LONDON LGBTQIA+ FILM FESTIVAL 2024 Takes Place 13 – 24 March at BFI Southbank and on BFI Player

Leave a comment